Problem Background

Seafood mislabeling is a broad societal problem that is pervasive in both the international and domestic fish trade, including for the world’s largest fish importer, the United States. The sources of seafood mislabeling are diverse. Mislabeling can be accidental if resulting from species misidentification, incorrect assignment of a common vernacular name1, or the loss of product information in the supply chain2. Mislabeling can also be intentional in order to increase profit or launder fish captured illegally into the legal food trade3,4. The complexity of the seafood supply chain make it difficult to identify where and when mislabeling occurs.

Harms of Seafood Mislabeling

The harms of seafood mislabeling are many. It reduces consumer confidence in the food we eat and weakens public trust of the seafood trade. It risks human health by inadvertently exposing to consumers to ciguatoxins or elevated mercury levels5-7, the latter a serious concern for children and pregnant women. It undermines conservation efforts, seafood certification programs, and distorts the actual abundance of seafood supplies to consumers and regulators. It capitalizes on illegal working conditions and exacerbates slavery on fishing vessels8.

Los Angeles and Seafood

|

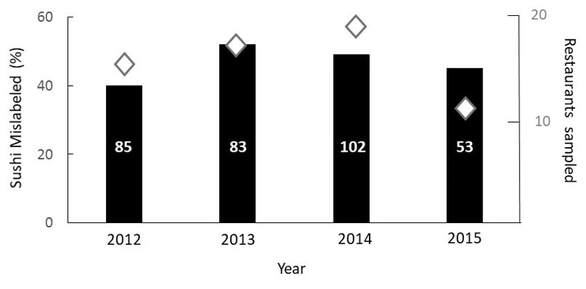

Los Angeles is one of the nation’s largest seafood markets and has a storied history with seafood, notably illustrated by the inclusion of a tuna on the county’s seal. Home to a headquarters of the world’s biggest tuna producer along with numerous seafood restaurants, sushi venues, fish markets and processors, seafood and the ocean are essential to the fabric of our city. Los Angeles, however, has also struggled with seafood mislabeling. Recent DNA-based surveys of seafood sold in LA’s restaurants revealed mislabeling rates up to 52%9-10 and consistently high year to year11.

|

The Los Angeles Seafood Monitoring Project

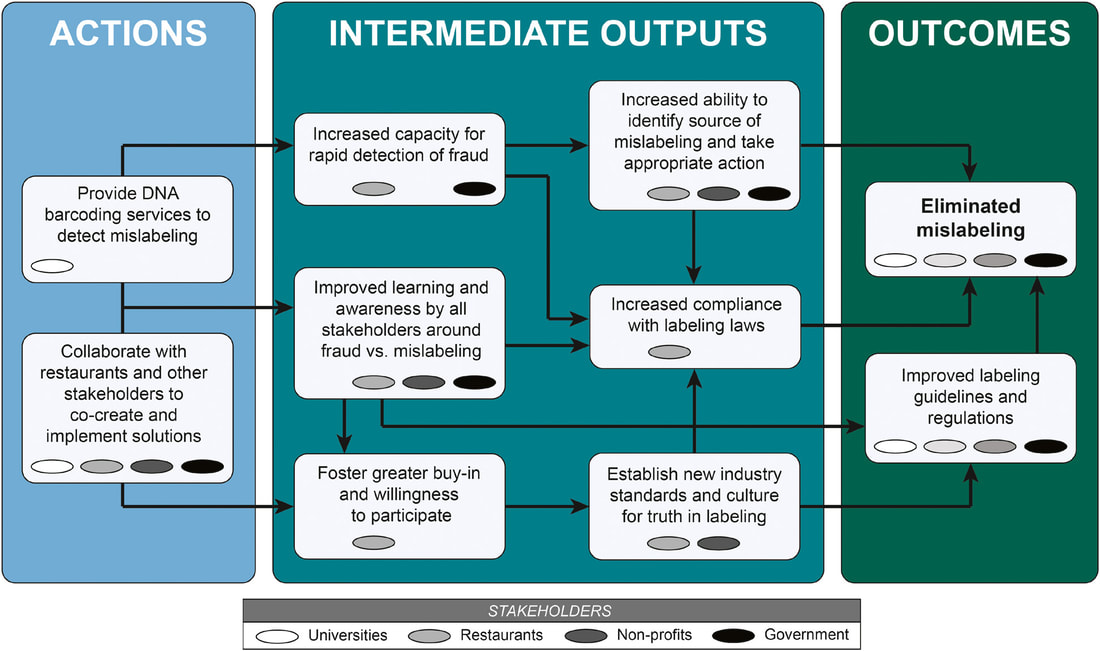

The Los Angeles Seafood Monitoring Project: A collaboration among local universities, non-profit organizations, and seafood restaurants and processors, as well as local, state, and federal government agencies, this project seeks to eliminate seafood mislabeling and increase seafood literacy across LA using a two-tiered approach:

- In cooperation with seafood restaurants and processors, the Project uses blind sampling and DNA barcoding to validate the identification of sold seafood. Sampling and DNA testing are grant supported and free to participating restaurants and processors. Taking a proactive and constructive approach, results from each source are confidentially reported back to individual restaurants and processors so they address any mislabeling. Furthermore, aggregated data is reported back to all Project collaborators and the public via press releases and publications.

- The Project works to clarify ambiguity in government labeling requirements for vendors that result in the majority of mislabeling. Engaging with the US Food and Drug Administration, the project proposes scientifically and culturally based revisions to “The Seafood List”. Reducing seafood mislabeling that results from limited FDA-recognized names will allow researchers and regulators to focus on cases of intentional seafood fraud.

References:

- Buck 2010. Congressional Research Service. Report RL34124.

- Cohen et al. 2009. J. Food Protection 72:810-817.

- Ogden 2008. Fish and Fisheries 9:462-472.

- Cawthorn et al. 2012. Food Research International 46:30-40.

- Perez-Arellano et al. 2005. Emerging Infectious Diseases 11:1981.

- Burger and Cochfeld 2004. Environmental Research 96:239-249.

- Jacquet and Pauly 2008. Marine Policy 32:309-318.

- Mendoza et al. 2016. Associated Press.

- Warner et al 2012. Oceana http://bit.ly/2MQEz4M

- Khaksar et al. 2015. Food Control 56:71-76.

- Willette et al. 2017. Conservation Biology 31:1076-1085.

|

Site powered by Jo M. Design and Prints

|